Translated by Eleni Nicolaou for xpressed.org

After three years in Greece, the IMF has triumphed in its mission assigned by PASOK [1] and the international banking system.

Since people learned to apologise the sense of honour was lost, an old Greek saying goes. In the case of the IMF, along with the sense of honour, millions of lives and trillions of dollars were also lost. Yet, in our humble opinion, the IMF should follow an old advice of Mahatma Gandhi: “Never apologise if you were right”.

Imagine a cook who, whenever entering the kitchen, follows to the letter a failed recipe. His clients suffer from diarrhea and some of them die. Each time, the cook makes an announcement admitting the mistakes of the recipe, asks humbly for forgiveness and goes back into the kitchen to prepare yet another lethal meal.

This is how several of its devotees but also its critics attempt to present the IMF, i.e. like a version of the Swedish chef from the Muppet show, who happens, in this case, to be holding the destinies of millions of people across the planet in his hands.

The famous error of the ‘multiplier’, admitted by the IMF (but not by its paid clerks in the political and journalist offices of Greece), is merely the latest example in a lengthy list of the international organisation’s mea culpa.

One can hardly find even a single case in which the Fund’s intervention did not have tremendous consequences for the real economy and was not followed by a public or secret admission of liability by its analysts.

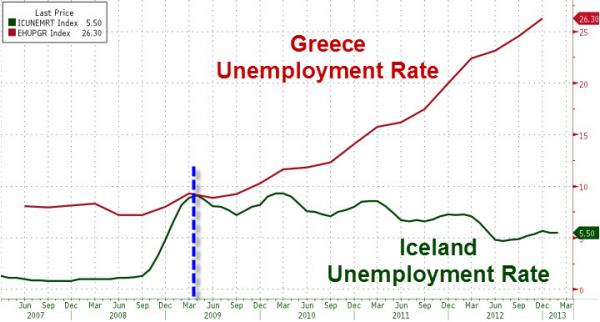

At the peak of its “failure”, the IMF publicly admitted that Iceland managed to survive the crisis by not following any of the rules set by its neoliberal priesthood –in fact, Iceland committed all the sins: from the payment default and the devaluation of the national currency up to the nationalisation of banks and the prohibition of free movement of capital.

In the case of Argentina, the Fund, through its reports, described one by one the mistakes that led to the collapse of the country. These are the very same “mistakes” that were imposed on Greece with the austerity policies, by denying a payment default and insisting on a monetary union that had nearly identical results with the binding of the Argentinean peso to the U.S. dollar.

However, are these reasons enough for the executives of the organisation to be apologising? Our answer is unequivocally negative because, contrary to the common perception of the “failed cook”, the IMF is in fact an excellent serial killer. The fact that every time they describe how they killed their victim does not, in any way, mean that they failed in their mission.

Two are the major hidden secrets around the IMF’s pompous mea culpa. First, they do not cost anything. Exclaiming “oops” after having reduced the life expectancy of millions of people by ten years –as was the case in Russia–, after having led thousands to suicide –as in Greece–, hundreds of children to begging –as in Argentina– and dozens of women to prostitution –as in Romania– does not constitute an honest apology. In fact, it is like spitting at the victims’ faces by declaring that they were unlucky enough to run into your meat grinder.

However, the major misunderstanding about the IMF apologies concerns the content of the issues for which they apologise. The international organisation can comfortably apologise for not rescuing the economies of countries that requested assistance, simply because it never intended to do so. As the Argentinean economist Claudio Katz explained to me, “The IMF is an instrument of the banks and, unless the attitude of the banks changes, the attitude of the IMF does not change”.

This “misunderstanding” –that the IMF’s role is to rescue countries– has its roots back in 1944, when the winners of World War II designed the new economic structure with the Bretton Woods Agreement. Reflecting the new equilibrium formed after the collapse of the British Empire, the new structure established the domination of the dollar as the global currency. The IMF and the World Bank, who were both born in the same year, would operate as regulators and guardians of the new system by intervening in order to cover irregularities in countries exchange rates and to help Europe smoothly integrate into the brave new world of American capitalism.

This conception, however, collapsed in the early ’70s along with the spirit of the Bretton Woods. Since then, the Fund ceased to deal with issues like the exchange rate stability and focused on the developing world that suddenly fell into the trap of debt. The IMF became, within a few years, the “tallyman” for the major financial institutions of the planet. “It was a constant looting from the countries of the North”, Hugo Arias, head of the Audit Committee of Ecuador and close associate of President Rafael Correa, explained to us earlier.

From that day onwards, the IMF’s target was not to help national economies escape the crisis but to keep them in a constant state of limbo by allowing foreign banks to suck the surplus value of labour. If the country collapsed financially –i.e. forced payment default– the banks would lose their money. If, on the other hand, the country recovered, it would get out of the control of the banks. Any of these two situations would be a failure for the IMF which would automatically lose its usefulness for the global financial system.

The South Korean example is typical of the way in which the IMF, in order to help those lender-banks like American Citibank and Chase Manhattan, led the country into the deepest recession since the financial crisis of 1997. Similar was the situation in Indonesia. According to a leak to the New York Times of a confidential IMF report, the Fund exacerbated the banking crisis of the country, blocking the efforts of a debt restructuring that could harm the interests of foreign lenders –exactly what Papandreou’s government did in the early years of the crisis under the orders of the IMF and the support of well-paid academics and journalists.

The exception was the case of Turkey whose geopolitical importance did not allow Washington to sacrifice it on the altar of the direct banking profit. “We never treated Turkey on purely economic grounds”, a Greek economist who was for years at the IMF HQ beside senior officers confided in me some years ago. It was the time shortly after the 2001 financial crisis, when the IMF and the World Bank generously offered 20 billion dollars.

In all other cases, the International Monetary Fund could generously apologise about the situation in which it left the national economy knowing that it had fulfilled its mission. Exactly as it has happened with Greece: the creditors managed to get rid of their toxic bonds, the labour law went back to 19th century conditions, public property is being sold off to the delight of Greek and foreign economic elites and the reactions are supressed by either the official police or the para-state fascist organisations fostered by PASOK and Nea Dimokratia [2]. The case of Greece is perhaps the greatest success in the history of the IMF. And no matter how hard they are apologising, they cannot hide their absolute triumph.

————————————

[1] PASOK: the so-called Socialist Party of Greece that has ruled the country for 22 years (1981-1989, 1993-2004, 2009-2012) during the 38 years following the fall of the dictatorship (1974)

[2] Nea Dimokratia: Right-wing party, head of the current coalition government